The Black Hills stretch across western South Dakota, northeast Wyoming, and southeast Montana and constitute a sacred landscape for the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne and Omaha.

To the Lakota, they are Paha Sapa, “the heart of everything that is.” The Black Hills were the casualty of one of the most blatant land grabs in U.S. history and continue to be the site of a legal and political confrontation.

Rick Two-Dogs, an Oglala Lakota medicine man, explains:

“All of our origin stories go back to this place. We have a spiritual connection to the Black Hills that can’t be sold. I don’t think I could face the Creator with an open heart if I ever took money for it.”

In the rolling, forested highlands of the Black Hills, four thousand archaeological sites spanning 12,000 years attest to a long relationship with native people. An oblong ridge circles the Black Hills, separating them from the surrounding prairie grasslands and making them “one of the most unusual environmental features in the United States,” according to anthropologist Peter Nabokov.

In the 1700s and 1800s, the Lakota ceremonial season began each spring with the stampede of buffalo from the Black Hills through Buffalo Gap. As the people followed the buffalo, they would go to places like Devils Tower and Bear Butte, their pathway forming the shape of a buffalo’s head. As Lakota scholar Vine Deloria Jr. tells it:

“In the spring, the people would follow the buffalo herd and they’d have to do a series of four ceremonies, the last one of which would either end up at Devils Tower or Bear Butte depending on what year it was and what the situation was.

This is written down now in a book on star knowledge” which illustrates the relationship between the constellations, land formations and movement of Lakota bands within the Black Hills. The Lakota believe that permanent occupancy of the Black Hills was set aside for the birds and the animals, not for humans.

The U.S. government initially tried to prevent settlement of the Black Hills, having signed the 1851 Treaty of Ft. Laramie, which promised 60 million acres of the Black Hills “for the absolute and undisturbed use and occupancy of the Sioux.”

White Settlers were aware that the Black Hills were sacred, considered the womb of Mother Earth and the location of ceremonies, vision quests, and burials. Initially, the newcomers accepted the fact that the Hills belonged to the Lakota—until gold was discovered.

When they heard the rumors of gold, they clamored for access to a vast area that had previously been avoided for fear of American Indian attacks and because of the 1851 Treaty.

Chase Iron Eyes Talks Sacred Land Black Hills Pe’Sla

with Ezra Miller & Sol Guy (2012)

In 1857, Lakota leaders gathered at Bear Butte to discuss the increasing number of white invaders in the Black Hills. As settlers continued to ignore the treaty boundaries of the Black Hills, and as the government began to build military posts within them to assure the safety of the westward-moving settlers, a second treaty was signed by a few Lakota leaders but did not fulfill the amount of Lakota men signature required to be valid.

It reduced their land base to 20 million acres. This was the 1868 Treaty of Ft. Laramie, the one to which all current legal arguments refer. In 1874, the government allowed General George Armstrong Custer to explore the Hills—ostensibly to find a place to build a fort, but Custer was accompanied by geologists and miners who confirmed the presence of gold.

This was a clear violation of even the second, more limited, treaty. The discovery of gold sparked a rush of miners and settlers, and the government tried to threaten the Lakota into selling their remaining 20 million acres.

When this didn’t work, Congress enacted a new treaty in 1877, with only 10% of the adult male Lakota population signing it, which seized the land, resulting in war and eventual defeat for the flakota—though Custer died for his sins in 1876 at Little Bighorn.

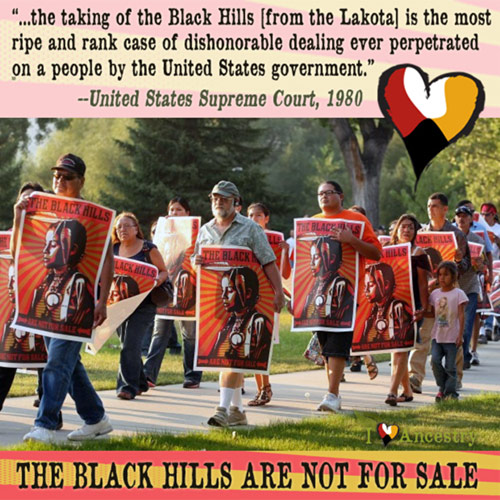

In the twentieth century, the Lakota began a concerted legal effort to reclaim the Black Hills. A federal judge who reviewed the case in the 1970s commented: “A more ripe and rank case of dishonorable dealing will never, in all probability, be found in our history.”

Now, the issue is whether tribal sacred lands taken in the nineteenth century can be bought and sold in the twenty-first. After a century of struggle to file claims in court against the illegality of the 1868 treaty, the Indian Claims Commission, the Court of Claims, and finally the Supreme Court in 1980 recognized the 8 Lakota Nations’ rights to the part of the Black Hills specified in the 1868 treaty.

But instead of ordering the government to return the land, the Claims Commission awarded a financial sum equal to the land’s value in 1877 plus interest. This sum now is a considerable amount but still much smaller than the value of the natural resources which have been extracted from the Black Hills, estimated at $4 billion.

The Lakota have refused to accept the money on the grounds that one cannot buy and sell sacred land. Says Johnson Holy Rock, a Lakota elder and former chairman of the Oglala Sioux, “We don’t think of the air and water in terms of dollars and cents.” Two political plans in the 1980s (one spearheaded by Senator Bill Bradley) to return 1.3 million acres of federal land in the Black Hills were defeated by the South Dakota congressional delegation, including Senator Tom Daschle.

US of A, Honor the Treaties!

Over the years, the Black Hills have experienced mining, logging, and recreational uses, often in violation of Lakota beliefs. Mining for gold, coal, and uranium pollutes water. Cyanide heap-leach gold mines, such as Homestake and Gilt Edge, use cyanide to extract gold from crushed ore.

The cyanide mixes with other chemicals, producing toxic chemicals that can leach into the groundwater. This sort of mining leaves huge open pits that scar the landscape, and frequently the companies are allowed to abandon the mines without cleaning up or restoring the land to its original state.

Two sacred places within the Black Hills, Bear Butte are on public land and are protected from natural resource extraction. However, both have endured conflicts over recreational use. Bear Butte, known as Mato Paha, has long been a site for ceremonies, vision quests, and important tribal meetings, though most Americans see the dramatic little mountain as just one of the many geographically stunning outcroppings in the Black Hills.

Aaron Huey & America’s Native Prisoners of War (TedTalks)

“Honor the treaties. Give back the Black Hills. It’s not your business what they do with them.”

~Aaaron Huey

Bear Butte became a South Dakota state park in 1961 and was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. To accommodate different uses of the park, the state created two different trails, one for hikers and one for native religious practitioners, which leads people to a designated ceremonial area.

Both trails are open to the public, however, non-native users are requested to stay on the trail and not disturb prayer bundles or individuals in ceremony.

In 1982 Lakota and Tsistsistas (Cheyenne) elders sued the state of South Dakota to prevent deeper incursions into the park to increase tourism, including a parking lot, roads, and campgrounds. They also sought to limit the state’s ability to establish new regulations requiring visitors, including traditional religious practitioners, to obtain permits.

The U.S. District Court’s opinion Fools Crow v. Gullet found that the American Indians could not have “full, unrestricted, and uninterrupted religious use of Bear Butte” because that would constitute the state establishing a religion, and because the state’s right to open the landmark to the public was protected under the First Amendment.

“…the taking of the Black Hills [from the Lakota] is the most ripe and rank case of dishonorable dealing ever perpetrated on a people by the United States government.”

-United States Supreme Court, 1980.

This was one of several cases in the 1980s which showcased the failure of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act to protect native religious practices on public land.

Other sacred places in the Black Hills include Buffalo Gap National Grasslands, Angostura Springs, Harney Peak, and Wind Cave National Park. The Lakota believe that the Wind Cave is the place where their ancestors emerged.

The site was occupied by Lakota activists and elders in 1981 to protest the 1980 Supreme Court decision that offered financial restitution for the taking of the Black Hills.

The same year marked the beginning of the occupation of Yellow Thunder Camp by American Indian Movement activists, an occupation which lasted for several years but was ultimately disbanded since they were denied permits for permanent structures.

“Every Indian outbreak that I have ever known has resulted from broken promises and broken treaties by the government.”

~Buffalo Bill

SOURCE: Based on materials from A Black Hills Report by Amy Corbin