Mary Brave Bird was an inspiring Brulé Lakota author and activist who was a member of the American Indian Movement during the 1970s and participated in some of their most publicized events, including the Wounded Knee Incident when she was 20 years old.

Mary Ellen Moore-Richard (Sep. 26, 1954 – Feb. 14, 2013) is known as Mary Brave Bird, also known as Mary Crow Dog and Mary Brave Woman Olguin. Mary Brave Bird and her life story were published in two books: Lakota Woman and Ohitika Woman. In these two books, written 15 years apart, Brave Bird told how the American Indian Movement (AIM) gave meaning to her life.

Lakota Woman, written under the name Mary Crow Dog, portrays her life from her birth to 1977, and Ohitika Woman written under her current name of Mary Brave Bird, covers events up to 1992 and adds new details to the earlier history.

Mary Brave Bird’s mother, Emily Brave Bird, had been raised in a tent in the village of He-Dog on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota, then taken to St. Francis Mission boarding school where she was converted to Catholicism.

While she studied nursing in Pierre, South Dakota, her four children were raised by their grandparents. Robert Brave Bird trapped in the winter and farmed in the summer. He was a descendant of the legendary warrior Pakeska Maza (“Iron Shell”), who became chief of the Wablenicha (“Orphan Band”) of the Brulé or Sicanju tribe of the Lakota Sioux.

Growing up on the Rosebud Reservation, Brave Bird faced poverty, racism, and brutality from an early age. Although she descended from a distinguished family, she was not taught a great deal about her heritage.

Her mother would not teach her her native language because, she said, “speaking Indian would only hold you back, turn you the wrong way.” She was sent to St. Francis Mission boarding school at the age of five, where she reported that nuns beat Indian students who practiced native customs or spoke their native languages. She later ran away from the school and began her teenage life drinking heavily and getting into fights.

While still a teenager, Brave Bird became involved in the protest activities of AIM, where she began to find new spirit and meaning in being Indian. In 1972, at the age of 16, she participated in the Trail of Broken Treaties march on Washington, D.C., after which protesters occupied the Bureau of Indian Affairs “BIA” building.

At that time, Brave Bird met Leonard Crow Dog, a Sicangu Lakota medicine man and spiritual leader who was active in AIM and taught her much about Native American Indian traditions. They were married the following year.

In February 1973 in Custer, South Dakota, Sarah Bad Heart Bull protested the release of the murderer of her son, Wesley Bad Heart Bull, and requested AIM’s help at the Custer courthouse.

When AIM protesters in Custer learned that the police had used violence on Bad Heart Bull’s mother, they rioted. The riot was followed by a meeting attended by medicine men Frank Fools Crow, Wallace Black Elk, Henry Crow Dog, and Pete Catches, all there to consider how to protest this incident.

At the time the Pine Ridge Reservation was calling for AIM to help protest the corrupt rule of Richard Wilson, the elected chairman of the reservation. Two elders suggested that they take a stand at Wounded Knee, where the U.S. cavalry had massacred hundreds of Sioux in 1890.

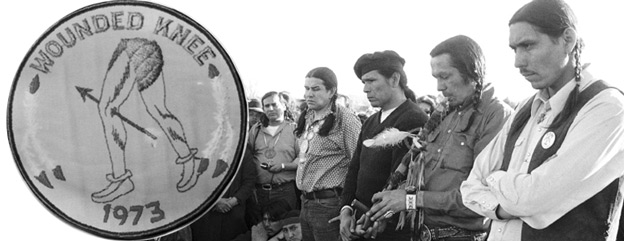

On February 27, 1973, under AIM leadership, a group of Native Americans, Brave Bird and Crow Dog among them did take a stand at Wounded Knee. They dug trenches, put up cinderblock walls, and became warriors.

The Wounded Knee Incident lasted 71 days. On March 12, surrounded by armored cars spewing bursts of gunfire, a declaration was drafted for the independent Oglala Nation proclaiming its sovereignty.

Two Native Americans Indians were killed, and many were wounded. Leonard Crow Dog treated the injured survivors with medicinal herbs; he led sunrise prayers and brought back the Ghost Dance for which his ancestors had bfeen slaughtered in 1890. For four days, and for the first time in 80 years, on sacred ground, they circled a cedar tree, dancing in the snow.

On April 11 Mary Brave Bird’s baby was born. She named him after Pedro Bissonette, a man who was killed by the tribal police for having founded the Oglala Sioux Civil Rights Organization (OSCRO).

The terrorist reprisals by Wilson’s “goons” (Guardians of the Oglala Nation) resulted in the deaths of 250 people, many of them children, on the reservation. Among those murdered was Delphine, Leonard Crow Dog’s sister, who was beaten to death.

The American Indian Movement (AIM) played a crucial role in Brave Bird’s new life. Without the organization, she lived in poverty and despair, coping with alcoholism, domestic violence, joblessness, and hopelessness.

Within the movement, she felt a sense of purpose. The alliance that AIM members made with the traditionalists restored for them their own ancient ways. Meanwhile, the tribal elders were given back their traditional roles as communicators of their culture. Brave Bird, sober, working for the cause, was heroic.

She learned from her work in the movement that pan-tribal (involving Native people from all tribal lines) unity can give spiritual power to even those who are treated as the dregs of society.

She described the movement’s ability to strengthen Native communities in her book Lakota Woman, which became a national best-seller, won a movie contract, and earned the American Book Award for best nonfiction.

Both Lakota Woman and Ohitika Woman retell the ancient myths and explain the meanings of many Native American ceremonies. As Brave Bird wrote, “AIM made medicine men radical activists, and made radical activists into sundancers and vision seekers….

It restored women’s voices and brought them into the tribal councils.” But while Lakota Woman is a breathless first-hand account of AIM’s early demonstrations from the perspective of a teenager who had been involved in heady events, Ohitika Woman presents them from the viewpoint of a mature woman, adding a needed historical background.

Brave Bird’s life did not necessarily become simpler with her new outlook, however. Even the large gap between their ages—Mary was 17 and Leonard was 31 when they married in 1973—was less of a problem than their cultural differences.

Leonard had to teach Mary the ceremonies, the use of healing plants, and reconcile her to the role of a medicine man’s wife. This involved feeding multitudes of uninvited guests at the feasts following every service.

It also meant never getting enough rest; as a tribal counselor, Leonard Crow Dog was always on call, traveling constantly, and taking his family along when he was summoned. Since he did not charge for healing and gave everything away, there was never enough money to feed the family.

Mary Brave Bird raised seven children. In addition to Richard, Ina, and Bernadette from Leonard’s first marriage, she had four more with him: Pedro, Anwah, June Bug, and Jennifer Louise.

On September 5, 1975, with helicopters whirring overhead, 180 agents broke into Crow Dog’s home and took him away in handcuffs. After three trials, he was sentenced to 23 years in prison for his political activities.

Mary Brave Bird addressed rallies to raise funds, but it took contributions of $200,000 from friends, Amnesty International, and the World Council of Churches to get him out of prison. Famed activist attorney William Kunstler argued on his behalf.

At Lewisburg Penitentiary Crow Dog’s cell was so small that he could not stand upright in it, while authorities at Leavenworth tried to disorient him by keeping a neon light glaring 24 hours a day. Filmmakers Mike Cuesta and David Baxter made a documentary about his imprisonment, and as a result a number of celebrities rallied to his support. When he returned to Rosebud, the entire tribe welcomed him with honoring songs.

After many separations and reconciliations, Brave Bird and Crow Dog divorced. Brave Bird married Rudi Olguin, a descendant of Zapotecs, Mexican Indians, on August 24, 1991, in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Together they had a daughter, Summer Rose.

In her books, Brave Bird tells what it means to be a Sioux woman—caught between the forces of tradition and the feminist movement, often subject to sexual harassment and degradation.

In Ohitika Woman, she speaks about her recurring problems with alcohol abuse, and the healing she has found in the Native American Church. Still, like many other feminists who are also Native Americans, she tends to place the economic, political, and legal struggles of Indian peoples before the pursuit of women’s rights.

She lived with her youngest children on the Rosebud Indian Reservation, South Dakota. Her 1990 memoir Lakota Woman won an American Book Award in 1991 and was adapted as a made-for-TV-movie in 1994.

Lakota Woman (The Movie): Siege at Wounded Knee starring Irene Bedard, Tantoo Cardinal, Pato Hoffmann, Joseph Runningfox, Lawrence Bayne, and Michael Horse and August Schellenberg. Directed by Frank Pierson. Produced by Fred Berner, Steven P. Saeta (executive producer), Lois Bonfiglio, Robert M. Sertner, Frank von Zerneck. Written by Bill Kerby, Richard Erdoes. Based on “Lakota Woman” by Mary Crow Dog. Music by Richard Horowitz. Cinematography: Toyomichi Kurita, Christopher Tufty. Editing by Katina Zinner. Distributed by TNT

SOURCE: Based on materials from “Native North American Biography” edited by Sharon Malinowski and Simon Glickman | Photo: Right: Ulf Andersen/Getty Images | Left: Richard Erdoes – Read Lakota Woman, The book