Florida Seminole Christmas Gift written by William Loren Katz adapted from Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage ©Atheneum, 2012 revised edition

On Christmas day 1837, the Africans and Native Americans who formed Florida’s Seminole Nation defeated a vastly superior US invading army bent on cracking this early rainbow coalition and returning the Africans to slavery.

The Seminole victory stands as a milestone in the march of American liberty. Though it reads like a Hollywood thriller, this amazing story has yet to capture public attention. It is absent from school textbooks and social studies courses, Hollywood and TV movies.

This daring Seminole story begins around the time of the American Revolution when 55 “Founding Fathers” broke free of British colonialism and wrote the immortal Declaration of Independence.

About the same time Seminoles, suffering ethnic persecution under Creek rule in Alabama and Georgia, fled south to seek independence. African runaway slaves who earlier escaped bondage and became among its first explorers welcomed them to In Florida.

The Africans did more than offer Seminole families a haven. They taught them in methods of rice cultivation they had learned in Senegambia and Sierra Leone, Africa.

Then the two peoples of color forged a prosperous multicultural nation and a military alliance ready to withstand the European invaders and slave-catchers. The Seminoles were led by such skilled military figures and diplomats as Osceola, Wild Cat, and John Horse.

This alliance drove US slaveholders to sputtering fury. They saw Seminole unity, prosperity, and guns as a lethal threat to their plantation system. Here was a beacon that enticed escapees and offered them a military base of operations. Further, these peaceful communities destroyed the slaveholder myth that Africans required white control.

And these armed Black and Indian communities lived a stone’s throw from the southern US border. The US Constitution of 1789 embraced slavery and protected slaveholder interests.

From George Washington to the Civil War slave owners sat in the White House two-thirds of the time, were two-thirds of Speakers of the House of Representatives, two-thirds of Presidents of the U.S. Senate, and 20 of 35 U.S. Supreme Court Justices.

With the support of their northern trading partners – merchants and businessmen, and the politicians who served them – slaveholders were able to direct US foreign policy.

Slaveholders and their allies kept up a drum-beat for US military intervention in Florida, and in 1811 President James Madison authorized covert US invasions by slave-catching posses called “Patriots.”

Then in 1816, General Andrew Jackson ordered General Gaines to attack the Seminole alliance and “restore the stolen negroes to their rightful owners.” A major US assault began on hundreds of people living in “Fort Negro” on the Apalachicola River.

As US Army Colonel Clinch sailed down the Apalachicola he wrote: “The American negroes had principally settled along the river and a number of them had left their fields and gone over to the Seminoles on hearing of our approach. Their cornfields extended nearly fifty miles up the river and their numbers were daily increasing.”

When a heated US cannonball hit “Fort Negro’s” ammunition dump, the explosion killed most of its more than three hundred defenders. The survivors were marched back to slavery. Then in 1818 General Jackson invaded and claimed Florida, the United States “purchased” it [$5,000,000] from Spain in 1819, and sent a US army of occupation for “pacification.”

But suddenly the US faced the largest slave revolt in its history, its busiest underground railroad station, and the strongest African/Indian alliance in North America. The multicultural Seminole forces carefully moved families out of harm’s way from 1816 to 1858 as they resisted the US through three “Seminole wars.” Today many Seminoles still claim they never surrendered.

In June 1837 Major General Sidney Thomas Jesup, the best informed US officer in Florida described the danger posed by the Seminole alliance: “The two races, the negro and the Indian, are rapidly approximating; they are identical in interests and feelings . . . .

Should the Indians remain in this territory the negroes among them will form a rallying point for runaway negroes from the adjacent states; and if they remove, the fastness of the country will be immediately occupied by negroes.”

Then on Christmas Day 1837, 380 to 480 Seminole fighters gathered on the northeast corner of Florida’s Lake Okeechobee ready to halt the armies of Colonel Zachary Taylor, a Louisiana slaveholder, and ambitious career soldier.

He was building a reputation as an “Indian killer.” Taylor’s troops included 70 Delaware Indians, 180 Tennessee volunteers, and 800 US Infantry soldiers.

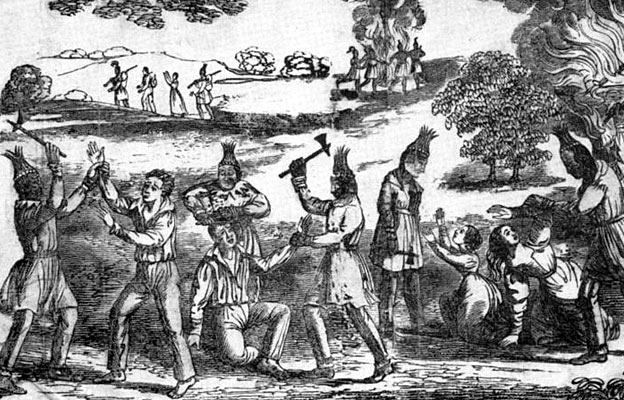

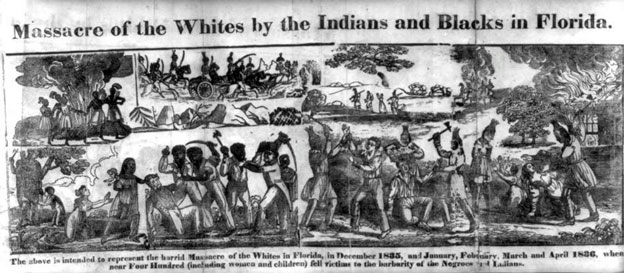

Detail from an 1836 engraving depicting events from the slave uprising during the Second Seminole War. Originally prepared for D.F. Blanchard’s 1836 narrative of the war. Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, LC-USZ62-366. The original engraver is not known, but portions of the work were derived from commonly available engraving blocks known as types.

As Taylor’s huge army approached Seminole marksmen waited perched in trees or hiding in tall grass. The first Seminole volleys sent the Delaware fleeing. Tennessee riflemen plunged ahead until a withering fire brought down their commissioned officers and then their noncommissioned officers. The Tennesseans headed home.

Then Taylor ordered the US Sixth Infantry, Fourth Infantry, and his own First Infantry Regiments forward. Pinpoint Seminole rifle fire brought down, he later reported, “every officer, with one exception, as well as most of the non-commissioned officers” and left “but four . . . untouched.”

That Christmas Day Colonel Taylor counted 26 U.S. dead and 112 wounded, seven dead for each slain Seminole, and he had taken no prisoners. After the two and a half hour battle, the Seminoles took to their canoes and sailed off to fight again.

Lake Okeechobee became the most decisive US defeat in more than four decades of Florida warfare. But after his survivors limped back to Fort Gardner, Taylor declared victory – “the Indians were driven in every direction.” The US Army promoted him and he later became the 12th president of the United States.

Lake Okeechobee took place during the Second Seminole War that took 1500 US military lives, cost Congress $40,000,000 (pre-Civil War dollars!) and left thousands of American soldiers wounded or dead of disease. Seminole losses were not recorded.

The truth of Lake Okeechobee remained buried. When President Taylor died in office, in Illinois Abraham Lincoln memorialized him on July 25, 1850. “He was never beaten,” Lincoln said, and added: “. . . in 1837 he fought and conquered in the memorable Battle of Lake Okeechobee, one of the most desperate struggles known to the annals of Indian warfare.”

A century and a half later noted Harvard historian and author Arthur Schlesinger Jr. wrote in The Almanac of American History: “Fighting in the Second Seminole War, General Zachary Taylor defeats a group of Seminoles at Okeechobee Swamp, Florida.”

The United States needs to face its past. Americans of all ages have a right to know and to celebrate the freedom fighters who built this country, all of them. Our schools, children, teachers, and parents deserve to learn about a daring Christmas day that has been too long neglected and distorted.

Note: Afro Native American or African Native American? People who call themselves “Black Indians” are people living in America of African-American descent, with significant heritage of Native American Indian ancestry, and with strong connections to Indian Country and its Native American Indian culture, social, and historical traditions. Black Indians are also called Afro Native American people, Black American Indians, Black Native Americans and Afro Native. Connecting with our ancestors.

SOURCE: Seminole Christmas Gift Adapted from Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage © Atheneum, 2012 revised edition by William Loren Katz.