The Rosewood Massacre

In a small Florida town, a lie was told.

A rumor was repeated.

A lynch mob was formed.

And a massacre began…

Honoring the ancestors who were slaughtered during the Rosewood Massacre that started on January 1, 1923. Never Forget. Explore a 14mn video below of the CBS 60 Minutes report presented by TV host Ed Bradley about the Massacre of African Americans in Rosewood Florida (1983).

The small town of Rosewood FL was established around 1870 in Levy County, Florida on a road leading to Cedar Key and the Gulf of Mexico. It took its name from the abundant red cedar that grew in the area. In 1890 the cedar depleted and many of the white families moved to Sumner, three (3) miles west of Rosewood FL.

By 1900 Rosewood FL had an African American majority of citizens. On the morning of January 1, 1923, Fannie Coleman Taylor of Sumner Florida, claimed she was assaulted by a black man.

Although she was not seriously injured and was able to describe what happened she allegedly remained unconscious for several hours due to the shock of the incident. No one disputed her account and no questions were asked.

It was assumed she was reporting the incident accurately. Sarah Carrier a black woman from Rosewood FL, who did the laundry for Fannie Taylor and was present on the morning of the incident, claimed the man that assaulted Fannie Taylor was her white lover.

It was believed the two lovers quarreled and he abused Fannie and left. However, in 1923 no one questioned Fannie Taylor’s account and no one asked Sarah Carrier about the incident. The black community claimed Fannie Taylor was only protecting herself from scandal.

A posse was summoned and tracking dogs were ordered by James Taylor, Fannie Taylor’s husband and the foreman at Cummer and Sons sawmill. The local white community became aroused at the alleged abuse of a white woman by a black man, which was an unpardonable sin against black men back then to look at a white woman.

James Taylor summoned help from Levy County and neighboring Alachua County, who was ending a staged Ku Klux Klan rally leading up to January 1, 1923, on the courthouse square in downtown Gainesville, where a large number of Ku Klu Klan members had been rallying and marching in opposition of justice for African American people.

A telegraph sent to Gainesville in regards to Fannie Taylor’s allegations provoked four to five hundred Klansmen that headed to Sumner at the appeal of James Taylor.

The ruins of the two-story shanty near Rosewood, Florida, in 1923 where black residents barricaded themselves and fought off a vicious white mob. First published in Literary Digest magazine on January 20, 1923 – Bettmann/CORBIS

With reaping tension displayed they willingly accepted the invitation and came to Sumner with a vengeance to participate at any cost necessary. They arrived enraged and combed the woods behind the Taylor’s home looking for a suspect.

Suspicion soon fell on Jesse Hunter an allegedly African American man who allegedly had recently escaped from a convict road gang. No proof of the escape was ever provided. The posse confronted Sam Carter at his home and Carter allegedly admitted to helping Hunter escape.

Allegedly the posse forced Carter to take them to the place where he last saw Hunter. Carter allegedly took the posse to where he parted ways with Hunter. When no trace of Hunter could be found the posse turned into an out of control lynch mob and tortured Carter, riddled him with bullets and hung him from a tree.

The posse continued their hunt in Rosewood FL. They found Aaron Carrier, cousin, and friend, to Sam Carter, in bed at his Sarah Carrier’s house, yanked him out of bed, tied a rope around his neck and dragged him behind a Model “T” from Rosewood to Sumner.

They tortured him, beat him with gun butts and kicked him until he lost consciousness before shooting him. Levy County Sheriff Bob Walker aborted the shooting when he yelled, “Don’t, I’ll finish the “N” off. The despicable “N” word saved Carrier’s life.

The posse returned to Rosewood to hunt for Sylvester Carrier. Sheriff Walker threw Aaron Carrier in his Model “T” taking him to Gainesville, Alachua County jail and begged Sheriff James Ramsey to hide Carrier from the public and his family until tempers settled down and suggested he get medical help for him.

Sheriff Ramsey brought in two local African American doctors, Dr. Parker and Dr. Ayers to treat Carrier for six months unknowingly to the public and his family. Fuming with anger because they had not found the attacker James Taylor sent Sylvester Carrier a message “We are coming to get you” the night of January 2nd, all hell broke loose in Rosewood when the mob returned with guns for a showdown, “to kill or be killed” because they were dissatisfied with the lack of success they anticipated.

The mob formed a “party of citizens” to discuss how to investigate and accomplish their mission to find and silence Sylvester Carrier, who had become a lightning rod for their anger. Unbeknownst to the posse Sylvester Carrier took heed to the threats and made contact with his Levy County friends who bravely traveled to Rosewood to help avert the planned ambush of its citizens.

After dark, the posse traveled to Rosewood prepared to kill or be killed. It had come down to Sylvester Carrier’s recruited men or the mob. The posse, intoxicated with moonshine and ignorance was met head-on with resistance and several were killed or injured, however, not accurately reported in the “all-white” 1923 newspapers. When the gun battle ended the posse that was able to return to Sumner, did return, leaving behind their guns. Others lay dead and wounded in Sarah Carrier’s yard.

When the massacre ended that morning before dawn Sylvester Carrier’s friends returned to their homes as they came, quietly “the back way” and went to work at Sumner sawmill and other places of employment the next day as if nothing happened. They never spoke openly about the Rosewood Massacre.

The posse started firing upon arrival. Henry Andrews, an Otter Creek resident, and C. Poly Wilkerson, a Sumner merchant were killed by Sylvester Carrier when they kicked in the door of his mother’s home, who they shot and killed through a window as she was walking through the house to quiet the children. Someone stationed in the house screamed, “Oh my God, Aunt Sarah’s been shot and Sylvester yelled, “SHOOT EVERYBODY, SHOOT!”

A black resident’s home in Rosewood Florida is shown in flames during the race riots in 1923. Photograph: Bettmann/Corbis

The posse realized too late they were encircled by resisting black men hiding in the dark pumping hails of lead to protect the Rosewood citizens, women and children, barricaded in the Carrier’s home.

Hails of gunfire came from under the house, from behind the house and behind the barn. Hours later, the fight ended in a blood bath that surprised the surviving posse as they mosey back to Sumner in disbelief, pain, and shame.

The broken posse returned to Sumner to regroup and wait for Sheriff Walker, who they refused to listen to earlier, bring them an update. However, gunshots being fired in the air at Rosewood FL kept the posse at bay until the Sheriff was able to finalize the escape route for the Rosewood Florida citizens.

For sure guns belonging to the posse, dead and injured, were left in Rosewood FL and unaccounted for in Sumner. The sound of shots being fired in Rosewood signified that there was still life in Rosewood and the posse was not in a hurry to return risking more lives in defense of Fannie Taylor’s horrific lies.

James Taylor sent the posse to Rosewood to participate in the attack on Rosewood Florida citizens although he never left Sumner surviving all physical harm. The posse now sought Sheriff Bob Walker to inquire about Rosewood’s state of affairs but the Sheriff was too busy negotiating with the Cedar Key train conductors, the Bryce Brothers, on how to move the citizens out of Rosewood safely.

January 3rd, when the shotgun firing ceased some Rosewood Florida citizens escaped into the swampland under the cover of fear, hiding out and waiting for the train to come and bring them to safety.

Other citizens hiding in Sarah Carrier’s house knew they had to leave their Rosewood Florida homes before the posse returned, therefore, they fled to store merchant John Wright’s home unannounced as instructed by Sheriff Bob Walker.

John Wright was in total shock to see his store customers arrived at his home seeking refuge. They were instructed to wait there in hiding until they heard back from the Sheriff who was traveling back and forth to Cedar Key, Sumner, and Rosewood in an effort to move them safely out of Rosewood on the 4 AM early morning train conducted by the Bryce Brothers from Bryceville, Florida.

Lexie Gordon sent her children to John Wright’s home for safekeeping although she was left in her home too ill to flee. When the posse returned to Rosewood FL days later to make an assessment of the damages they revengefully shot and killed her. Gordon’s home and other Rosewood Florida homes were burglarized before burning them down.

James Carrier, an animal trapper, who had suffered a stroke a few years earlier was the husband to Amma Carrier, the father of Aaron Carrier, and brother-in-law to Sarah Carrier, was ordered to dig his own grave and was shot and killed because he knew nothing about what was happening in Rosewood FL when he returned from his animal traps deep down in the woods.

On Sunday morning the posse returned and one by one angrily burned the last remaking structures belonging to the African American community. The homes were burned because they did not want the public to know the real truth, “more than two whites were killed.”

Therefore, they burned the evidence, bodies and all. “Until the Lion tells his own story, the tale of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.”

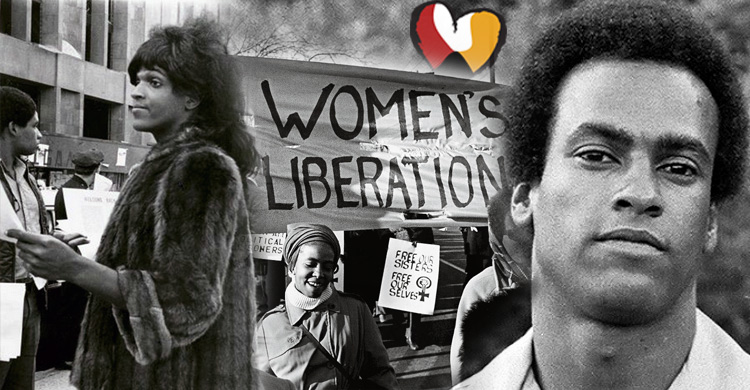

CBS 60 Minutes: The Massacre in Rosewood Florida (1983)

Powerful 14mn documentary by TV host Ed Bradley where he goes back in time, through eye-witness testimony, to the “Old South” and reconstructs the day that Rosewood Florida died in January 1923.

IMPORTANT: We disagree with the number of victims the TV host keeps referring to as a maximum of 40. We believe the number of deaths during that horrific event is way more significant than what has been reported in that documentary.

Rosewood Massacre Aftermath

On February 12th, 1923 a special grand jury was empaneled to investigate the massacre. After twenty-five white and allegedly eight black witnesses testified the jurors reported that they could find no evidence on which to base any indictments.

The Black community of Rosewood never returned. Many left for other cities and counties losing touch with each other never sharing the Rosewood story with family members.

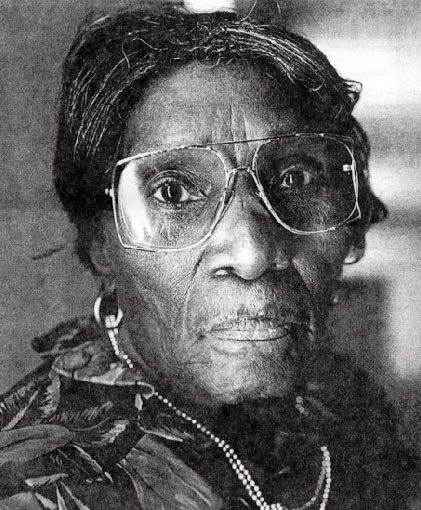

And a number changed their names including Aaron and Mahulda Gussie Brown Carrier, Rosewood’s historians and school teacher. She was born Mahulda Gussie Brown on May 5, 1894, in Archer, Alachua County, Florida.

She married Aaron Carrier December 19, 1917. After the Rosewood tragedy, they moved more than fifteen times escaping accumulated fear. They changed their name to Aaron and Mahulda G. Carroll.

They even changed their birth dates. Mahulda Gussie Brown Carrier/Carroll lived in fear until death April 25, 1948, Tampa, Florida at the Clara Frye Hospital. Her name is listed “Mahulda G. Carroll” on her headstone.

Lizzie Polly Robinson Brown Jenkins’ mother strongly encouraged her to preserve Rosewood history never forgetting her Rosewood sister, Mahulda Gussie Brown Carrier/Carroll’s suffrage. Jenkins’ Rosewood reconstructive research is dedicated to the Rosewood survivors and descendants in memory of Rosewood culture.

January 1, 2000, a plaque bearing Mahulda Gussie Brown Carrier’s name hangs on the porch of the Archer Train Depot, the same depot Carrier exited January 4, 1923, driven by the Bryce Brothers.

The African American residents of Rosewood lost all of their personal possessions during the massacre and lost their property after the massacre. A few returned in 1957 to claim their property and were told the property had been sold and were ordered to leave town. Their land was confiscated under tax sales and not until 1994 did the state or any public entity offer an apology or make any compensation.

SOURCE: Based on materials from The Real Rosewood Foundation, Inc. by Lizzie Jenkins – Retired Educator/Author, Founder & President of The Real Rosewood Foundation.