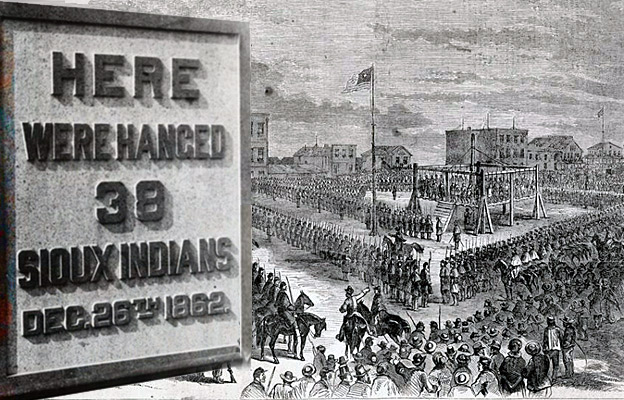

US History’s largest hanging execution of 38 + 2 Dakota Ancestors in Mankato, Minnesota: December 26, 1862

Never forget that this day after Christmas is somber for Dakota American Indians marking a travesty of justice over 156 years ago when 38+2 of their ancestors were executed in what is known to be the largest mass hanging execution in U.S. history. Their trials were conducted unfairly in a variety of ways. They were executed at Mankato, Minnesota on December 26, 1862.

Overshadowed by the Civil War raging in the East, the hangings in Mankato, Minnesota, on December 26, 1862, followed the often overlooked six-week U.S.-Dakota war earlier that year led by Dakota Chief Ta-Oyate-Duta Little Crow (c.1810 – July 3, 1863) — a war that marked the start of three decades of fighting between Native American Indians and the U.S. government across the Plains.

“The trials of the Dakota were conducted unfairly in a variety of ways. The evidence was sparse, the tribunal was biased, the defendants were unrepresented in unfamiliar proceedings conducted in a foreign language, and authority for convening the tribunal was lacking. More fundamentally, neither the Military Commission nor the reviewing authorities recognized that they were dealing with the aftermath of a war fought with a sovereign nation and that the men who surrendered were entitled to treatment in accordance with that status.”

~Carol Chomsky, Associate Professor

University of Minnesota Law School

President Abraham Lincoln and government lawyers reviewed the trial transcripts of 303 men. As Lincoln would later explain to the U.S. Senate:

“Anxious to not act with so much clemency as to encourage another outbreak on one hand, nor with so much severity as to be real cruelty on the other, I ordered a careful examination of the records of the trials to be made, in view of first ordering the execution of such as had been proved guilty of violating females.”

When only two men were found guilty of rape, Lincoln expanded the criteria to include those who had participated in “massacres” of civilians rather than just “battles.” He then made his final decision and forwarded a list of 39 names to Sibley.

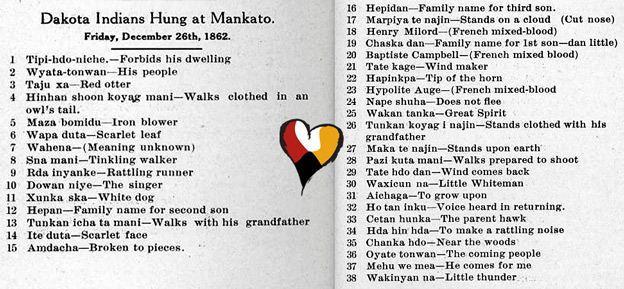

List of Dakota names from Marion Satterlee. Account of the Massacre by the Dakota Indians of Minnesota in 1862

On December 26, 1862, 38 Dakota men were hanged at Mankato, MN

At 10:00 am on December 26, 38 Dakota prisoners were led to a scaffold specially constructed for their execution. One had been given a reprieve at the last minute. An estimated 4,000 spectators crammed the streets of Mankato and surrounding land. Col. Stephen Miller, charged with keeping the peace in the days leading up to the hangings, had declared martial law and had banned the sale and consumption of alcohol within a ten-mile radius of the town.

As the men took their assigned places on the scaffold, they sang a Dakota song as white muslin coverings were pulled over their faces. Drumbeats signaled the start of the execution. The men grasped each others’ hands. With a single blow from an ax, the rope that held the platform was cut.

Capt. William Duley, who had lost several members of his family in the attack on the Lake Shetek settlement, cut the rope. After dangling from the scaffold for a half-hour, the men’s bodies were cut down and hauled to a shallow mass grave on a sandbar between Mankato’s main street and the Minnesota River.

Before morning, most of the bodies had been dug up and taken by physicians for use as medical cadavers. Following the mass execution on December 26, it was discovered that two men had been mistakenly hanged.

“Wica??pi Wasteda?pi” (We-chank-wash-ta-don-pee), who went by the common name of Caske (meaning the first-born son), reportedly stepped forward when the name “Caske” was called and was then separated for execution from the other prisoners. The other, Wasicu, was a young white man who had been adopted by the Dakota at an early age. Wasicu had been acquitted.

“After the hanging of 38 Dakota warriors plus Little Six and Medicine Bottle, the Dakota were exiled from their ancestral homelands. We were divided. Some were shipped to prison camps in Iowa, where the men and women were separated and soldiers raped the women. Others were marched to Crow Creek, SD bare feet in the snow. Some were held at a concentration camp in Sisseton, SD where children died of cholera daily. Some Dakota escaped to Spirit Lake and Canada. Others out ran the cavalry on foot, to find Sitting Bull. We became outlaws by virtue of being alive. They called my ancestors ‘redskins’ and put a bounty on the scalps of Dakota men, women, and children.”

~Ruth Cankudutawin Hopkins

DAKOTA 38 + 2 (Full Movie): Jim Miller’s Dream

This documentary film about Jim Miller in the spring of 2005, a Native spiritual leader, and Vietnam veteran found himself in a dream riding on horseback across the great plains of South Dakota. Just before he awoke, he arrived at a riverbank in Minnesota and saw 38 of his Dakota ancestors hanged.

At the time, Jim knew nothing of the largest mass execution in United States history, ordered by Abraham Lincoln on December 26, 1862. “When you have dreams, you know when they come from the creator…

As any recovered alcoholic, I made believe that I didn’t get it. I tried to put it out of my mind, yet it’s one of those dreams that bothers you night and day.” Now, four years later, embracing the message of the dream, Jim and a group of riders retrace the 330-mile route of his dream on horseback from Lower Brule, South Dakota to Mankato, Minnesota to arrive at the hanging site on the anniversary of the execution.

“We can’t blame the wasichus anymore. We’re doing it to ourselves. We’re selling drugs. We’re killing our own people. That’s what this ride is about, it is healing.”

This is the story of their journey- the blizzards they endure, the Native and Non-Native communities that house and feed them along the way, and the dark history they are beginning to wipe away.

“I watched only half because my tears kept me from seeing. This is one of the most important films ever made. It should be required viewing for every American citizen from middle school through old age. These brave, courageous people and those who helped them on their journey and those who made this film are the most honorable human beings I have witnessed in a long time. Words cannot possibly express my gratitude and humility, so accept my deepest bows for this inspiration.”

~Thomas Hodges, Opelika, AL

SOURCE: Based on materials at usdakotawar.org from Isaac V. D. Heard, History of the Sioux War and Massacres of 1862 and 1863, NY: Harper & Bros., 1863 | Isch, John. The Dakota Trials: The 1862-1864 Military Commission Trials: Including the Trial Transcripts and Commentary. New Ulm, MN: Brown County Historical Society, 2012 | CC BY-NC-SA 3.0