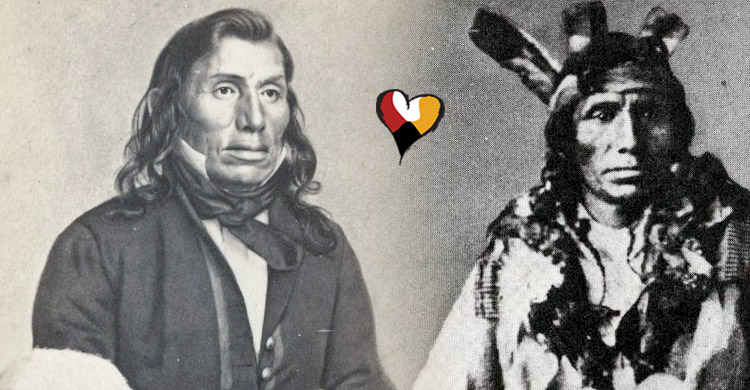

George Bonga of Ojibwe and African heritage was a fur trader who was one of the first Americans of African descent born in the state that is now called Minnesota. George Bonga is a strong example of the blurred boundaries and concepts of race during the end of the fur trade.

George Bonga (August 20, 1802 – 1874) was born near Duluth, Minnesota. George was the son of Pierre Bonga (Jamaican?), and an Ojibwe (Anishinaabe) mother. George Bonga was well educated, as he attended school in Montreal and spoke English, French, and Ojibwe.

Read also: Edmonia Lewis, American Sculptor of Haitian and Ojibwe Heritage

George Bonga in Minnesota

Bonga was part of the mixed racial and cultural groups that connected trading companies and Native American Indians. He became a fur trader for the American Fur Company before establishing his own trading post and often worked as an advocate for the Ojibwe in their dealings with trading companies and the government.

Bonga also worked as a wilderness guide. He was famous in the Lake Superior region in Minnesota due to his strength of character and talents as well as for being, as his younger brother Stephen claimed “One of the first two black children born in the state.” George’s brother, Stephen Bonga, was also a notable fur trader and translator in the region.

Many Americans of African descent in the United States were enslaved in the early 1800s, but Bonga was a free man. His grandfather, Jean Bonga, had been either an enslaved African or an indentured servant in Michigan and was freed after the British soldier’s death. George Bonga’s grandfather and grandmother became fur traders.

George Bonga was described as standing over six feet tall and weighing 200+ pounds. Reports said that he would carry 700 pounds of furs and supplies at once.

George Bonga’s father, Pierre Bonga, was a fur trader and a guide for the famous explorer Alexander Henry Jr. George learned wilderness skills from his father and mother and followed in the family tradition of fur trading. Bonga worked for the American Fur Company in the 1820s. In the 1830s, he traded at posts throughout northern Minnesota.

A noteworthy incident in Bonga’s life occurred in 1837. That year, an Ojibwe man named Che-Ga Wa Skung, was accused of murdering a white man at Cass Lake, known as Red Cedar Lake at the time. Though initially in custody, Che-ga-wa-skung escaped.

According to contemporary accounts, Bonga trailed the man over five days and six nights during the winter, eventually catching him. Bonga brought the man back to justice at Fort Snelling for trial. In one of the first criminal proceedings in Minnesota, Che-ga-wa-skung was tried and acquitted.

Bonga’s actions were unpopular with some of the Ojibwe, but he continued living with or near them for the rest of his life. Five years after the incident he married Ashwewin, an Ojibwe woman, and they had four children together.

While working for the fur company, Bonga drew the attention of Lewis Cass, Governor of Michigan Territory. Cass hired Bonga as an interpreter for negotiations at a treaty council held in Fond du Lac territory with the Ojibwe.

Bonga also spoke against white men who treated Ojibwe trappers unfairly. Bonga wrote letters on behalf of the Ojibwe complaining to the state government about individual Native American Indian agents in the region.

PDF: George Bonga’s Letter to Indian agent Joel Bean Bassett in 1866

In this 1866 letter to Joel B. Bassett, an Indian agent, Bonga complains about the behavior of the local Indian agent, Major Clark, who is refusing to approve any trading licenses beyond a few favored traders.

PDF: George Bonga’s Letter to Henry Rice in 1872

In this 1872 letter, George Bonga writes to Henry Rice, an early political leader who was Minnesota’s second delegate to congress. Bonga is clearly responding to a query from Rice about Bonga’s history.

Bonga’s letters, which point out both his connections to the white government and the Ojibwe, further illustrate the ways that Bonga traversed cultural boundaries during this period.

In 1868, he again served as an interpreter for Indian agent Joel Bean Bassett in negotiations with the Mississippi Band of Ojibwe at White Earth in Minnesota. Bonga’s signature is on treaties brokered in 1820 and 1867, respectively. The Bonga family remained in the fur trade up until the 1860s.

Well respected in the Minnesota region, George Bonga lived among Native American Indians for the rest of his life, helping with their fair treatment as they were pushed from their lands by European Americans.

According to the reports of some of those travelers, Bonga enjoyed telling stories of early Minnesota and singing. As the fur trade declined, Bonga turned to the Indian trade.

He monitored annuity payments to the Ojibwe and worked with local Indian agents. His business changed with the times and by 1870 he was a retired dry goods merchant.

With residences in Minnesota’s Lac Platte, Otter Tail, and Leech Lake, Bonga was quite prosperous and a lavish host, as recounted in the memoirs of Judge Charles Flandreau after an extended visit in 1858.

Bonga married twice in the course of his lifetime, first to Nahgahnashequay then to Baybahmausheak Ashwewin, both from the Ojibwe Nation. He had five children: Peter, William, Jack, Susan, and George.

George Bonga died at Leech Lake in 1874. Though the spelling is different, Bungo Township in Cass County, Minnesota is named after Bonga’s family.

Read also: Edmonia Lewis, American Sculptor of Haitian and Ojibwe Heritage

“No tree has branches so foolish as to fight among themselves.”

~Ojibwe proverb

Note: Afro Native American or African Native American? People who call themselves “Black Indians” are people living in America of African-American descent, with significant heritage of Native American Indian ancestry, and with strong connections to Indian Country and its Native American Indian culture, social, and historical traditions. Black Indians are also called Afro Native American people, Black American Indians, Black Native Americans and Afro Native. Connecting with our ancestors.

SOURCE: Compiled material from Minnesota Historical Society and WilliamlKatz.com and his book Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage © Atheneum, 2012 revised edition. Photo taken ca. 1870 by Charles Alfred Zimmerman