John Brown: A White Role Model

by William Loren Katz

John Brown (May 9, 1800 – December 2, 1859) was executed by the state of Virginia on December 2, 1859. This year (2006) a PBS documentary film continued an effort that began even before his execution to sully his reputation. Why? He was a white man who gave his life, fighting slavery but he did so before Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation.

He was a premature “emancipationist.” However, two years after John Brown’s death Union soldiers marched into the South singing of the man—” his truth goes marching on.” In the year 2000 PBS film finds no truths about Brown worth repeating.

The documentary begins with a long, slow scene showing Brown being led to the gallows and ends with a long slow scene showing him being led to the gallows. This could seem like a warning to similarly inclined white people, and the public deserves better.

Brown was a devout Christian who saw slavery as violence and whose favorite Biblical quote was “Remember them that are in bonds, as bound with them.” He swore his entire family to the anti-slavery struggle; led armed bands that rescued enslaved people and was an active agent of the underground railroad.

In 1856 Brown fought slaveholders’ fire with rifle fire in the Kansas Civil War. He was not a man to be trifled with. When President James Buchanan offered a $250 reward for Brown’s capture, he offered $2.50 for Buchanan’s.

In 1858, he met in Canada with dozens of African Americans, including the father of Black nationalism, Martin R. Delany, to develop his liberation plan. The next year Brown led five African Americans, and 17 whites including three of his sons, to seize the government arsenal at Harper’s Ferry. Their goal was to arm enslaved people, help them reach the Allegheny mountains, help them wage a war against bondage.

Enslaved African Americans rallied to Brown’s forces at Harper’s Ferry, but this has long been hidden from the public. Federal troops under Captain Robert E. Lee who commanded a Marine detachment surrounded the arsenal and boxed in Brown’s men.

Ten of the raiders died fighting, five escaped, including one African American, and Brown and the others were captured. Virginia tried and convicted Brown of treason. Attending his execution were Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and John Wilkes Booth, three men soon to embark on more massive treason of their own.

School textbooks have not forgiven Brown for his interracial band, his fearlessness, and his armed response to slavery. The textbook, “The American Pageant” by Bailey and Kennedy describes Brown’s exploit as “insane,” “mad exploit,” “crack-brained scheme,” “bloody purpose.”

African Americans saw Brown differently. They saw a man who looked at slavery as they did. Haiti, born of a slave rebellion, named a boulevard after him. W.E.B. DuBois called his biography of Brown his favorite book.

Benjamin Quarles wrote a book on the positive response to the man and his deed by African Americans. In 1964, Malcolm X asked if would admit a white man to his new organization, said “John Brown.” This year Harlem’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture honored Brown with a special program, and I was a speaker there.

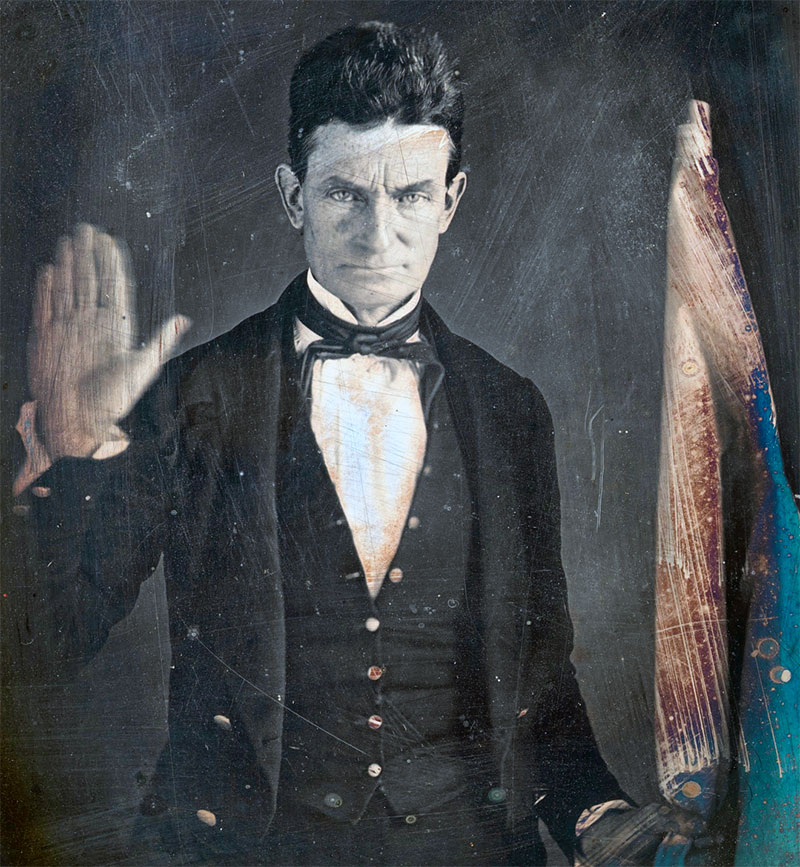

Photography by African-American photographer Augustus Washington in Springfield, Massachusetts, c. 1846–47. Brown is holding the hand-colored flag of Subterranean Pass Way, his militant counterpart to the Underground Railroad.

Brown was born the year that Gabriel organized a massive slave plot to capture Richmond, Virginia, and the year Nat Turner, who would lead a massive slave revolt in Virginia, was born. Brown pledged his family and his life to the destruction of bondage and white supremacy.

At each step of the way, he involved African Americans in his plans. At the Brown dinner table house, Black children for the first time heard white people refer to their parents as “Mr. Smith” and “Mrs. Smith.”

John Brown’s raid proved that free and enslaved people of color if given a chance would rise against bondage. It further proved that some whites were ready to join them and fight to the death.

When captured, Brown refused any effort to save his life by pleading insanity and turned down a rescue plan. He used the forty days between his capture and his execution to focus national attention on slavery’s evil. His last note before his death said prophetically, “I am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with Blood.”

In death, Brown became a martyr to millions. Garibaldi called him a “Jesus.” Victor Hugo called him “an apostle and a hero,” and on behalf of citizens of France gave his family a John Brown medal. “America has been hanged in John Brown,” wrote a Polish patriot.

Black people declared a Martyr’s Day and in slave Baltimore placed his picture on their walls. Henry David Thoreau said, “He taught us how to live” and abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison said, “He told us what time of day it was, it was high noon.” Frederick Douglass said, “John Brown began the war that ended American slavery and made this a free Republic.”

Sixteen months after Brown was hanged, slaveholders began a civil war that took 600,000 lives. Before it was over 200,000 African Americans served in the Union Army and Navy, and in 39 major battles, they turned the tide against the Confederacy. Black troops carried the message of Gabriel, Turner, and Brown as they liberated their sisters and brothers.

During the John Brown program at the Schomburg Center, a Haitian American asked me why Haiti has a John Brown Boulevard, and the United States does not. He raised a very important question.

More articles and information about William Loren Katz ‘s 40 books.

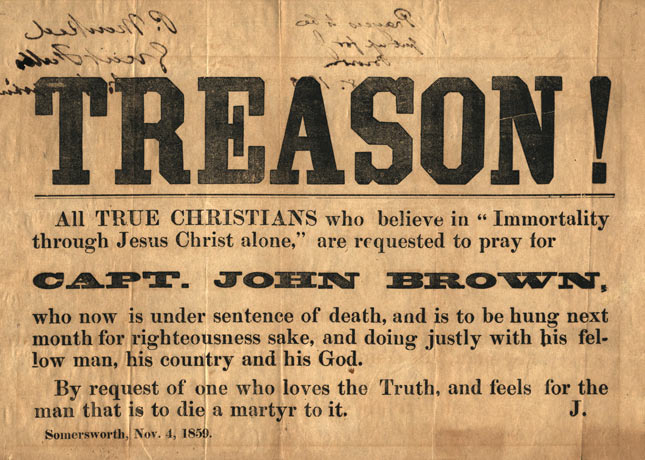

Never Forget during his sentencing, on November 2, 1859 John Brown made the following statement:

I have, may it please the court, a few words to say.

In the first place, I deny everything but what I have all along admitted, — the design on my part to free slaves. I intended certainly to have made a clean thing of that matter, as I did last winter, when I went into Missouri and took slaves without the snapping of a gun on either side, moved them through the country, and finally left them in Canada. I designed to do the same thing again, on a larger scale. That was all I intended. I never did intend murder, or treason, or the destruction of property, or to excite or incite slaves to rebellion, or to make insurrection.

I have another objection; and that is, it is unjust that I should suffer such a penalty. Had I interfered in the manner which I admit, and which I admit has been fairly proved (for I admire the truthfulness and candor of the greater portion of the witnesses who have testified in this case), — had I so interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great, or in behalf of any of their friends — either father, mother, sister, wife, or children, or any of that class — and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been all right; and every man in this court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment.

The court acknowledges, as I suppose, the validity of the law of God. I see a book kissed here which I suppose to be the Bible, or at least the New Testament. That teaches me that all things whatsoever I would that men should do to me, I should do even so to them. It teaches me further to “remember them that are in bonds, as bound with them.” I endeavored to act up to that instruction. I say, I am too young to understand that God is any respecter of persons. I believe that to have interfered as I have done — as I have always freely admitted I have done — in behalf of His despied poor, was not wrong, but right. Now if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments. — I submit; so let it be done!

Let me say one word further.

I feel entirely satisfied with the treatment I have received on my trial. Considering all the circumstances, it has been more generous than I expected. I feel no consciousness of my guilt. I have stated from the first what was my intention, and what was not. I never had any design against the life of any person, nor any disposition to commit treason, or excite slaves to rebel, or make any general insurrection. I never encouraged any man to do so, but always discouraged any idea of any kind.

Let me say also, a word in regard to the statements made by some to those conncected with me. I hear it has been said by some of them that I have induced them to join me. But the contrary is true. I do not say this to injure them, but as regretting their weakness. There is not one of them but joined me of his own accord, and the greater part of them at their own expense. A number of them I never saw, and never had a word of conversation with, till the day they came to me; and that was for the purpose I have stated.

Now I have done.

Never Forget John Brown (May 9, 1800 – December 2, 1859) was an American abolitionist and a True Hero who used violent actions to fight slavery. During 1856 in Kansas, Brown commanded forces at the Battle of Black Jack and the Battle of Osawatomie. Brown’s followers also killed five pro-slavery supporters at Pottawatomie. In 1859, abolitionist John Brown led a small group on a raid against a federal armory in Harper’s Ferry in an attempt to start an armed slave revolt and destroy the institution of slavery. Brown was arrested, tried, and hung.

SOURCE: Based on materials of Annals of America. © 1968,1976 Encyclopedia Brittanica, Inc. and William Loren Katz