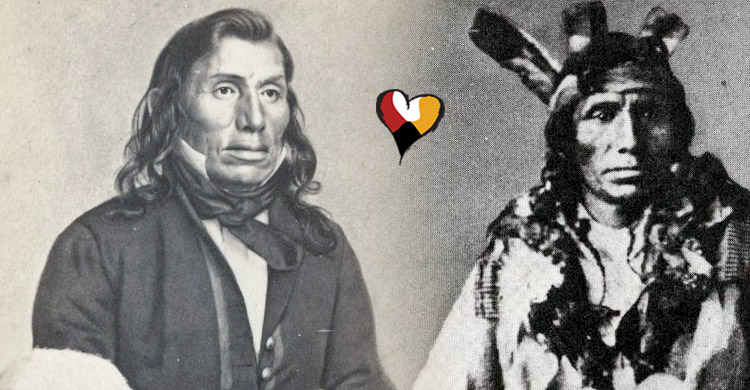

Chief Ta-Oyate-Duta Little Crow in “Indian Heroes and Great Chieftains” by Charles A. Eastman (Ohiyesa).

Dakota Chief Ta-Oyate-Duta “Little Crow” (c.1810 – July 3, 1863) was the eldest son of Big Thunder also named Little Crow. It was on account of his father’s name, mistranslated Crow, that he was called by the whites “Little Crow.” His real name was Taoyateduta, His Red People. He was the Dakota Chief who led the Dakota War in 1862. It is important to note that 38 + 2 Dakota Ancestors in Mankato, Minnesota were executed in what is known to be the largest mass hanging execution in US history on December 26, 1862.

—

Little Crow was an intensely ambitious man and without physical fear. He was always in perfect training and early acquired the art of warfare of the Indian type. It is told of him that when he was about ten years old, he engaged with other boys in a sham battle on the shore of a lake near St. Paul.

Both sides were encamped at a little distance from one another, and the rule was that the enemy must be surprised, otherwise the attack would be considered a failure. One must come within so many paces undiscovered in order to be counted successful. Our hero had a favorite dog which, at his earnest request, was allowed to take part in the game, and as a scout he entered the enemy camp unseen, by the help of his dog.

As a young man, Little Crow was always ready to serve his people as a messenger to other tribes, a duty involving much danger and hardship. He was also known as one of the best hunters in his band. He was hereditary Chief of the Mdewakanton Kapozia band of the Sioux, at a time when the Sioux were facing the greatest and most far-reaching changes that had ever come to them.

At this juncture in the history of the northwest and its native inhabitants, the various fur companies had paramount influence. They did not hesitate to impress the Indians with the idea that they were the authorized representatives of the white races or peoples, and they were quick to realize the desirability of controlling the natives through their most influential chiefs.

Little Crow became quite popular with post traders and factors. He was an orator as well as a diplomat, and one of the first of his nation to indulge in politics and promote unstable schemes to the detriment of his people. More and more as time passed, this naturally brave and ambitious man became a prey to the selfish interests of the traders and politicians.

The immediate causes of the Sioux outbreak of 1862 came in quick succession to inflame to desperate action an outraged people. The two bands on the so-called “lower reservations” in Minnesota were Indians for whom nature had provided most abundantly in their free existence. After one hundred and fifty years of friendly intercourse first with the French, then the English, and finally the Americans, they found themselves cut off from every natural resource, on a tract of land twenty miles by thirty, which to them was virtual imprisonment.

By treaty stipulation with the government, they were to be fed and clothed, houses were to be built for them, the men taught agriculture, and schools provided for the children. In addition to this, a trust fund of a million and a half was to be set aside for them, at five percent interest, the interest to be paid annually per capita. They had signed the treaty under pressure, believing in these promises on the faith of a great nation.

However, on entering the new life, the resources so rosily described to them failed to materialize. Many families faced starvation every winter, their only support the store of the Indian trader, who was baiting his trap for their destruction. Very gradually they awoke to the facts.

At last, it was planned to secure from them the north half of their reservation for ninety-eight thousand dollars, but it was not explained to the Indians that the traders were to receive all the money. Little Crow made the greatest mistake of his life when he signed this agreement.

The murder of a white family near Acton, Minnesota, by a party of Indian duck hunters in August 1862, precipitated the break. Messengers were sent to every village with the news, and at the villages of Little Crow and Little Six, the war council was red-hot.

It was proposed to take advantage of the fact that north and south were at war to wipe out the white settlers and to regain their freedom. A few men stood out against such a desperate step, but the conflagration had gone beyond their control. There were many mixed bloods among these Sioux, and some of the Indians held that these were accomplices of the white people in robbing them of their possessions, therefore their lives should not be spared.

Many Lightnings, who was practically the leader of the Mankato band (for Mankato, the chief, was a weak man), fought desperately for the lives of the half-breeds and the missionaries. “The chiefs had great confidence in my father, yet they would not commit themselves since their braves were clamoring for blood.”

Little Crow had been accused of all the misfortunes of his tribe, and he now hoped by leading them against the whites to regain his prestige with his people, and a part at least of their lost domain. Little Crow declared he would be seen in the front of every battle, and it is true that he was foremost in all the succeeding bloodshed, urging his warriors to spare none.

He ordered his war leader, Many Hail, to fire the first shot, killing the trader James Lynd, in the door of his store.

“Indian Heroes and Great Chieftains” by Charles A. Eastman (Ohiyesa)

—

On July 3, 1863, Nathan Lamson Killed Little Crow. He later received a standard bounty for the scalp of a Dakota, plus an addition $500 bounty when it was discovered the remains were that of Little Crow. Little Crow’s body was transported back to Hutchinson where it was again mutilated by the citizens. His body was dragged down the town’s Main Street while firecrackers were placed in his ears and dogs picked at his head. After their celebration, the town disposed of the body in an alley, where ordinary garbage was regularly thrown. The Minnesota Historical Society received his scalp in 1868, and his skull in 1896.

In 1971, Little Crow’s remains were returned to his grandson Jesse Wakeman (son of Wowinapa) for burial. A small stone tablet sits at the roadside of the field where Little Crow was killed.