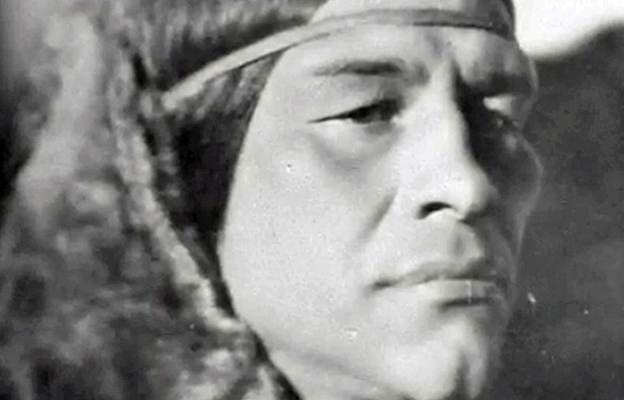

Long Lance, a Brilliant human being, of African, Native & Caucasian heritage that taught society, how foolish it is to judge a human being by their ethnicity. Sadly, the culture that Long Lance lived in was not ready for that message.

Born Sylvester Clark Long (December 1, 1890 – March 20, 1932), Long Lance was an outstanding American journalist, writer, and actor from Winston-Salem, North Carolina who became internationally prominent as a spokesman for American Indian causes.

Although the American South saw him more like a Black American than American Indian, Sylvester Long knew that the racial divisions of the United States of the time meant that he stood a better chance to make something of himself as an American Indian than as a Black American and the response of many of his ‘friends’ on the revelation of his ‘true’ mixed racial identity says more for the flaws and hypocrisy of American society of the time than anything about the character of Long Lance himself…

He became famous following the publication of his bestselling autobiography, purportedly based on his experience as the “son of a Blackfoot chief”. He was of mixed Tuscarora, Cherokee, Black and white heritage, at a time when Southern society imposed binary divisions of Black and white in a racially segregated society.

Long Lance had ambitions that were larger than what he saw of his future in Winston-Salem, where his father Joseph S. Long was a janitor in the school system, and his family was classified as Black. Long Lance was of mixed Tuscarora and white ancestry on his mother Sally Carson Long’s side, and mixed Cherokee, white and black ancestry on his father’s.

In that segregated, binary society, Black Americans had limited opportunities. Long Lance first left North Carolina to work as an American Indian in a “Wild West Show”. Here he had a chance to learn from Cherokee elders. He continued to build on his American Indian ancestry “to avoid the confines of racialism in the South and to secure a community of his choice.”

In 1909, Long Lance applied as a half-Cherokee to gain admittance to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School and was accepted, partly because of his ability to speak Cherokee. He reduced his age to get admission and the chance for a good education.

He graduated in 1912 at the top of his class, which included other prominent young American Indians, such as Jim Thorpe and Robert Geronimo, a son of the famous Apache warrior.

Long Lance entered the St. John’s and Manlius Military academies in Manlius, New York with a full musical scholarship, based on his performance at the Carlisle Indian School. He graduated in 1915. At that stage, he had begun to call himself Long Lance and had earned a stereotypical nickname “chief” as the only American Indian in his class.

He decided to try for the West Point and appealed to President Woodrow Wilson, whose office endorsed his application. He began there, but left in 1916 to enlist in the Canadian Expeditionary Force in Montreal (237th Battalion, CEF)and was shipped to France to fight in World War I.

After being wounded twice, he was transferred to a desk job. Long Lance returned to Canada as an acting sergeant in 1919, requesting discharge at Calgary, Alberta. He spent his next decade on the Plains, where he became deeply involved in learning about and representing Indian life.

He worked as a journalist for the Calgary Herald. Canada had de facto segregation and a climate in which the government had discouraged Black immigration from the US. “It is not surprising that in such a climate…Long Lance felt that he was safer and that he could go further, by disavowing any connection, cultural or racial, to blackness.”

He presented himself as a Cherokee from Oklahoma and claimed he was a West Point graduate with the Croix de Guerre earned in World War I. For the next three years as a reporter, he portrayed issues on Indian life.

He visited Indian reserves and wrote articles defending Indian rights. He criticized government treatment of Indians and openly criticized Canada’s Indian Act, especially their attempts at re-education and prohibiting the practice of tribal rituals.

In recognition of his work, in 1922 the Kainai Nation (also called Blood tribe) of the Blackfoot Confederacy adopted Long Lance. They gave him the ceremonial name, “Buffalo Child”, which he began to use thereafter.

To a friend, Long Lance justified his decision to assume a Blackfoot Indian identity by saying it would help him be a more effective advocate, that he had not lived with his own people since he was sixteen, and now knew more about the Indians of Western Canada.

In 1924, Long Lance became a press representative for the Canadian Pacific Railway. By 1926 he handled press relations for their Banff Springs Hotel. Through these years, Long Lance also entered the civic life of the city, by joining the local Elks Lodge and the militia, and coaching football for the Calgary Canucks.

These activities would not have been possible at that had he represented himself as a Black citizen. He was a successful writer, publishing articles in national magazines, reaching a wide and diverse audience through Macleans and Cosmopolitan.

By the time he wrote his autobiography in Alberta in 1927, Buffalo Child Long Lance represented himself as a full-blooded Blackfoot. Cosmopolitan Book Company commissioned Long Lance’s autobiography as a boy’s adventure book on Indians.

It published Long Lance in 1928, to quick success. In it, Long Lance claimed to have been born a Blackfoot, son of a chief, in Montana’s Sweetgrass Hills. He also said that he had been wounded eight times in the Great War and been promoted to the rank of captain.

The popular success of his book and the international press made him a major celebrity. The book became an international bestseller and was praised by literary critics and anthropologists. Long Lance had already been writing and lecturing on the life of Plains Indians.

His celebrity gave him more venues and caused him to be taken up as part of the New York party life. More significantly, he was the first American Indian admitted to the prominent Explorers’ Club in New York.

In 1929, Long Lance entered the film world, starring in the silent film “The Silent Enemy: An Epic of the American Indian”, which showed traditional ways of Ojibwe people. Hunger was portrayed as the major enemy in the hunting culture of northern Canada.

He promoted the cause of American Indians. The movie attempted to depict Indian tribal life more realistically than in previous films and was released in 1930. It was filmed in Quebec more than 40 miles from cities and used many First Nation and American Indian actors and extras.

An American Indian advisor to the film crew, Chauncey Yellow Robe, became suspicious of Long Lance and alerted the studio legal advisor. Long Lance could not explain his heritage to their satisfaction, and rumors began to circulate. An investigation revealed that his father had not been a Blackfoot chief, but a school janitor in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Some neighbors from his home town testified that they thought his background may have included African ancestry, which meant by southern racial standards, he was Black. Although the studio did not publicize its investigation, the accusations led many of his socialite acquaintances to abandon Long Lance.

Author Irvin S. Cobb, a native of Kentucky active in New York, is reported to have lamented,

“We’re so ashamed! We entertained a nigger!”

Historians have described Long Lance as a fraud, but he had American Indian ancestry on both sides of his family: Croatan and Cherokee, he looked Indian, and he knew enough Cherokee to use it when being admitted to the Carlisle Indian School.

His representation was not all a pose. He was not of the Blackfoot tribe but studied their traditions deeply while living on the Great Plains.

In his Being and Becoming Indian: Biographical Studies of North American Frontiers, late 20th-century historian James A. Clifton called Long Lance “a sham” who “assumed the identity of an Indian”, “an adopted ethnic identity pure and simple.”

The story of Long Lance has provided late twentieth century authors with much to mull over in questions of personal and ethnic identity. Donald B. Smith, a history professor, and biographer described Long Lance as “passing as an Indian”, but he confirmed Croatan ancestry on his mother’s side and Cherokee ancestry on his father’s.

He was American Indian, Black and white, trying to escape from outrageous limitations imposed on his Black Americans in his native North Carolina state. Smith noted that Long Lance was deeply involved in supporting Indian issues of the day and representing First Nations causes in Canada, as well as trying to best represent American Indian traditions in the US.

When Smith’s book was published in paperback in 2002, the title was changed to Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance: The Glorious Impostor (rather than “Impersonator”.)

Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance was found dead in Los Angeles, California in March 1932. He had died from a self-inflicted gunshot. In his will, he left all his remaining assets to St. Paul’s Indian Residential School in Alberta, Canada.

Most of his papers were willed to his friend, Canon S.H. Middleton. They were acquired, along with the Middleton papers, by J. Zeiffle, a dealer who sold the papers to the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, Canada in 1968.

In death, as in life, Long Lance remained dedicated to improving the lives of American Indian people…

Documentary “Long Lance” by Bernie Dichek (1986) 55 min

Note: Afro Native American or African Native American? People who call themselves “Black Indians” are people living in America of African-American descent, with significant heritage of Native American Indian ancestry, and with strong connections to Indian Country and its Native American Indian culture, social, and historical traditions. Black Indians are also called Afro Native American people, Black American Indians, Black Native Americans and Afro Native. Connecting with our ancestors.

SOURCE: Based on materials from glenbow.org and Wikipedia