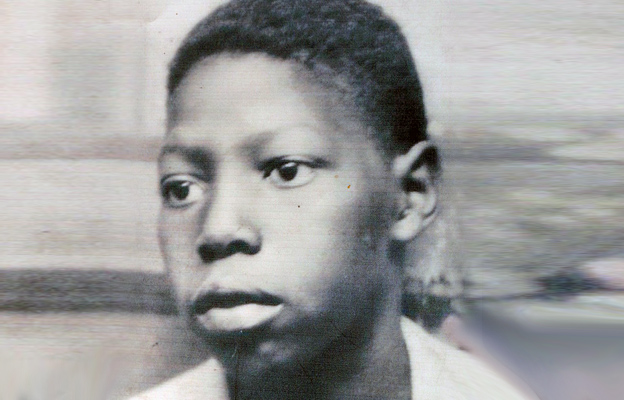

Johnny Robinson Jr. who was 16 when he was killed, shot in the back by a white police officer during the unrest following the infamous church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama on September 15, 1963.

Racial violence broke out on the streets that afternoon, leading to two other less well-known killings that day. The Death of 16-year-old Johnny Robinson Jr. and 13-year-old Virgil Lamar Ware.

While the names of the four little girls killed at church the morning of Sunday, September 15, 1963, are etched in the nation’s memory, the name of Johnny Robinson Jr. from the area killed that day in racial violence is absent from history books.

Murdered by police Johnny Robinson Jr. was with a group of boys near a gas station in the 800 block of 26th Street that afternoon around 3 p.m., and everyone on the street was on edge after the bombing of Sixteenth Street Baptist Church.

Carloads of young white people were driving by, taunting the young black people on the street with chants like “two, four, six, eight, we don’t want to integrate,” said James Jemison, a friend of Johnny’s who was playing football nearby.

Today, FBI files in the archives of a Birmingham library finally offer more detail about what happened that somber afternoon. Johnny Robinson was hanging around with a few other black teenagers near a gas station on 26th Street.

It was a tense scene. White kids drove by, waving Confederate flags and tossing soda pop bottles out car windows. They exchanged racial slurs with Johnny Robinson and his group.

Witnesses told the FBI in 1963 that Johnny was with a group of boys who threw rocks at a car draped with a Confederate flag. The rocks missed their target and hit another vehicle instead. That’s when a police car arrived.

Officer Jack Parker, a member of the all-white police force for almost a dozen years, was sitting in the back seat with a shotgun pointed out the window. The police car blocked the alley.

FBI agent Dana Gillis describes what happened next.

“The crowd was running away and Mr. Robinson had his back [turned] as he was running away,” Gillis says. “And the shot hit him in the back.”

As expected, other police officers in the car offered differing explanations for the shooting to protect the officer. But other witnesses with no ties to the police said they heard two shots and no advance warnings.

Some news reports at the time concluded, mistakenly, that the kids had been tossing rocks at the police. A local grand jury reviewed the evidence back in 1963 but declined to move forward with any criminal prosecution against the white police officer. A federal grand jury reached the same conclusion a year later, in 1964.

Jack Parker, the officer who shot Johnny, was head of a Fraternal Order of Police lodge and was against integration of the police force. Parker died in 1977.

Doug Jones who is white and a lifelong resident of the area prosecuted two of the men responsible for the sixteenth street baptist church bombing when he was the U.S. attorney in Birmingham during the Clinton administration. Jones said he’s not surprised the Johnny Robinson case went nowhere.

“Those cases involving the excessive force or discretion of a police officer are very, very difficult to make even in today’s world much less in 1963 where you would most likely have an all-white, probably all-male jury who was going to side with that police officer by and large,” Jones says.

Birmingham civil rights leader, Rev. C. Herbert Oliver, called Washington to say the government wasn’t protecting black children. Instead, Oliver said, law enforcement seemed to be more interested in shooting them.

Johnny’s sister, Diane Robinson Samuels, remembers arriving at the hospital late in the afternoon on that awful day.

“My mama was coming out the door, and she said, ‘Your brother dead, your brother dead,’ “ Samuels, now 62, recalls. “I think it was about four, five cops was there. And she was just beating on them. With her fists, just beating, ”Y’all killed my son, y’all killed my son.’ “

In 2009, the FBI reopened the investigation as part of its effort to figure out whether it could prosecute old civil rights cold cases from the 1960s. Dana Gillis, who was responsible for the bureau’s civil rights program in Birmingham at the time, delivered the letter to the Robinson family telling them that the bureau could not indict anyone in the case as white police officer Jack Parker had died in 1977.

While the Robinsons now know more about what happened to their brother, it is understandable that they still aren’t satisfied.

“We didn’t get no closure,” Samuels said. “We ain’t got nothing but heartaches.”

The city of Birmingham finally proclaimed Johnny Robinson a foot soldier in the civil rights movement.

SOURCE: Written and compiled by I Love Ancestry based on materials from npr.org by Carrie Johnson and al.com by Jon Reed.